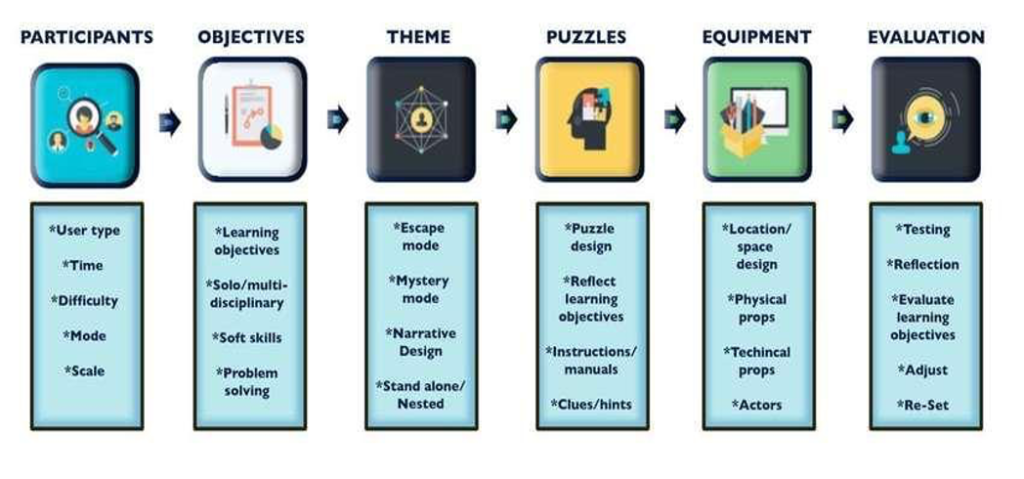

The module will work through the process of designing an educational escape room from scratch.

Following the stage process suggested from the Trans Disciplinary Methodology by Arnab & Clarke, the Participants step is broken down into five areas for educators to consider at the start of designing their educational escape room.

1. User Type: User needs assessment is carried out to determine player demographic and educational needs.

2. Time: Length of experience. Can be a short experience of 15 minutes or a longer experience that lasts multiple days.

3. Difficulty: It is important to consider who the intended user is in order to scale/manage the puzzles’ difficulty according to players’ educational and/or professional levels i.e. college students, undergrads, postgrads, doctorates, and staff.

4. Mode: Choose mode of experience such as; Cooperation based: Players work together to solve/escape the experience vs Competitive based: Players compete to be the first to figure out the objectives.

5. Scale: Choose number of participants the game is to be designed for.

In Grain 2 we explained the first area – User type.

In Grain 3 we will continue with explanation of area 2 – Time and 3 – Difficulty.

Time. Setting the game duration

Most of the Educational Escape Rooms last 50 to 60 minutes including the briefing and debriefing activities. The 60-minute time limit allows for a sufficient number of puzzles to be used, offers sufficient time for students to work as a team, and fits into one hour of instruction. Some escape rooms have a time limit of 30-50 minutes and others last 20-25 minutes. These shorter time limits can be attributed to time constraints; when the available time is restricted to one hour, games have to be shorter to include briefing/debriefing sessions or to be reset if the activity has to be conducted in multiple time slots for large groups (Walsh and Spence, 2018). Additionally, shorter games require less development time. Games lasting 75-120 minutes are less frequent because they can result in student fatigue (Hsu et al., 2009). However, longer games can give educators the opportunity to use more meaningful challenges that require more time and effort to be solved (López-Pernas et al., 2019).

The availability of time for an escape room game will have an impact on the planning and implementation. In practice, if it takes 60 minutes to play an ER, 15 minutes will be dedicated to briefing at the beginning and end, as well as time to tidy up and reset the room in-between games.These need to be considered when thinking about how the game will be carried out. Of course, while commercial escape rooms are usually around one hour in length, specific time lengths may be more appropriate in a classroom setting.

The time limit in an educational escape game also depends on:

- the age of the students,

- the curriculum,

- the learning goals,

- the location – lab, classroom (during regular classes or extracurricular clubs), museum.

In a school, classrooms are used for different classes and courses. Consequently, teachers have limited time to set up and clear away activities (Cain, 2019; Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019). A resulting design criterion for educational escape rooms is to enable fast and easy handling.

Timing issues: having a short amount of time to set the game when running events in tight schedules is often stressful for ER creators.

Possible time and space constraints include available space (the room might be small; or there might be multiple rooms available), or time (e.g. if the escape room must be played within a specific school period), or the availability of specific equipment, etc.

The time limit is not always mandatory. It depends on the learning goals and could be adapted to the tasks, learners’ needs, and learners’ level of concentration. Time can be stretched to multiple sessions or days in order to avoid the negative effects of time pressure in the process.

Difficulty. Managing the game difficulty

This is where consideration of your intended users should play a part. You might want to scale the difficulty of puzzles for different levels of students such as primary school students, secondary school students, college students, undergraduates and postgraduates. Depending on the theme of the escape room, you can use different scaling terms for the students to choose from. Theme: super-hero; scaling: “Civilian, police, side-kick, superhero” for example or you can use an element of the theme and have more of them as you go higher in difficulty. Alternatively, you could create a series of experiences and label the difficulty as easy, medium, hard or extreme mode, and allow your students to select what they would like to try. This approach also gives users an added level of control over their play.

Once the user type of participants in the escape room have been identified and the learner analysis has been performed, it is necessary to determine the difficulty of the puzzles for the different learning styles and types of participants.

Like any game, it is important to balance the difficulty in an escape room so that it is neither frustrating because it is too hard, nor it is boring because it is too easy. This can be difficult for team games, particularly where there is a range of abilities in the team or the class overall.

A good escape room will be designed so that there are a variety of different puzzles and levels so that everyone can be engaged with a fitting task. Another way to manage the level of difficulty is through the use of hints and clues. It is always tempting when watching people struggle with a difficult puzzle to give hints early on, but this should be avoided. Consider how you will provide hints, whether players will be given on request or when you think they are needed. Will the number of clues be limited, and will you give straight clues or cryptic clues that form puzzles in themselves? Will you plan the hints in advance and work from a script or make them up ad-hoc?

In order to fit into the constraints discussed above, the time, difficulty and linearity of the game must be adjusted. To do this, a number of parameters must be taken into account:

- the number of levels

- the difficulty of the riddles

- the number of clues and their access facility

- the number of multiple clues

- the guidance of the teacher

- the progress level of the game

- the distribution of clues

- the link between clues and riddles

- the number of participants

- time

The first constraint is how to divide learners according to available time slots and rooms. This will set the number of participants as well as playing time. Teams in educational escape rooms tend to be bigger. This is mainly due to constraints imposed by classroom size, time, and facilities. Conducting an escape room activity with large groups means that several sessions have to take place, which can be a logistical nightmare. As a result, team size compromises often have to be made, which can affect student participation.

Once the game time has been defined, it will be necessary to adjust the difficulty and the linearity of the game so that learners are able to finish the Escape game in the expected time. Making the game too hard and nonlinear will lead to the failure of the majority of the learners; conversely, creating a game too easy and too linear will lead to success of almost all learners long before the expected time. The difficulty of the parameterization is to find the right dosage between these two parameters.

As for the number of levels, at least one is needed. Note that associating the validation of a level with the discovery of new elements (clues, rooms, and other objects) generates a non-negligible gain of interest of the players. It is therefore advisable to put several clues according to the overall playing time.

Then, if the riddles are varied, this will play on the flow state (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) (Chen, 2007) of the learner. Putting a riddle that is too difficult at the beginning of the game can discourage the learners. A simple idea is to organize the riddles by increasing difficulty. Other alternatives are possible, for example: alternate a simple riddle with a more complex one to give a bit of break to learners between two complex riddles. In addition, this will lead to an increase in motivation since they will solve the simple riddles faster, which will encourage them to face a more complex riddle.

Regarding the number of clues and their ease of access: the more clues, the more it is possible to divide the problems and have combinations of clues. It therefore increases the probability that students will try false leads. In addition, the more hidden the clues are, the longer the search time. If the clues are hidden too well, they may not be found, so it is advisable to hide the clues carefully. For example, important clues can be hidden in a simple hiding place; however, optional clues can be hidden better.

It is also important to focus on the number of multiple clues (used several times in the game): it is useful to specify before the start of the session whether this type of clue is present within the game or not, this will influence the difficulty of the game. In their absence, used clues can be put aside, which reduces the possibilities and simplifies the use of clues.

The guidance of the teacher allows each group to progress at roughly equivalent speeds. This can generate frustration if learners get stuck on/have difficulty with a riddle. For example, since the pedagogical interest of the search is low, if they take too much time to find a hidden clue, it is advisable to help the learners in order not to slow down their advancement. It is therefore unnecessary for a group of players to lose too much time searching for clues. Secondly, a riddle posing a problem for a group of students will require the help of the supervisor for its resolution. Ideally, the teacher should be able to bring each group to the end or close to the end of the game within the time allotted.

Another important aspect is to implement a way for students to position themselves in the advancement of the activity. It is optional but it allows for better time management by learners and gives them a motivation to know that they are approaching the end of the game.

In regards to the distribution of the clues paired with the link between clues and riddles, this link is a concrete explanation of the fact that a clue belongs to a riddle. These two aspects affect the linearity and the difficulty of the game. If the link between the clues and the riddles is too strong and the clues are directly usable, this makes the game too linear and breaks the multiplayer aspect, which may induce the boredom of some learners. On the contrary, if there are too many clues and riddles in parallel, the game will be very difficult and will require more thinking and pooling by the team. This will make the game much more time consuming. It is important to find a good balance between the clues and the riddles to make the game challenging and not to let the players get lost, nor guiding them through a simple path.

Then, it is important to create enough content to occupy all participants at the same time throughout the game time. This will force the team to divide the tasks and prevent one student from leading and others from moving around only without doing anything.

Finally, the game should be achievable within a limited time from the viewpoint that the participants are all engaged with a different task. In practice, this is never the case, it is necessary to search, the pooling of the clues, the collaboration and the common reflection.