Definition of puzzles and gained skills

An Escape Room is essentially one big puzzle consisting of smaller, gradational and logically connected puzzles that players need to crack, in order to solve the room.

Oxford dictionary defines puzzles as “a game that you have to think about carefully in order to answer or do it”. The thought process you need to go through to successfully solve a puzzle is also reflected in the skills and competences that people of all ages can gain, such as problem-solving, critical thinking, memorization, judgement and visual-spatial reasoning (i.e. how to place different parts in the bigger picture) (USA Today, 2020). Additionally, puzzles cultivate basic skills, like goal setting and a sense of achievement, physical skills, such as fine motor skills and also teamwork (Miles Kelly, 2018). The latter is especially encountered in collaborative settings, as is an Escape Room, where players have to combine their knowledge and competences by choosing puzzles that have some connection with the story.

Basic structure of Escape Room puzzles

According to Wiemker et al (2015, p. 3), every puzzle is composed of a simple three-step loop: a challenge, its solution and the reward. The challenge is what players need to overcome, so as to find the solution to the puzzle and get the reward. In turn, this either leads to the next puzzle or to the resolution of the room. Picture, for instance, a locked safe that requires a key to open. In this case, the challenge is to find the key that unlocks the safe; the solution is the key found hidden somewhere in the room; and the reward will be the contents of the locked safe. For the progression of the game, it’s important to define both the challenge and the reward in a clear way, in order to motivate the students and give them an obvious indication of whether they tackled the obstacle and how they can proceed.

Characteristics of Escape Room puzzles

Another thing to pay attention to when designing your puzzle is the difficulty of the challenge itself: if it’s too easy, the students will become bored and stop playing, while if it’s too difficult, they will get frustrated and quit their efforts. Instead, the goal is to enable the players to become fully immersed and spatially present in the game, in an effort to help them focus on the task at hand and experience the room to the fullest. Wiemker et al. also refer to this state as “flow”, which is achieved when the participants are “challenged and entertained” (2015, p.11). As such, a well-designed puzzle should keep them on the borderline between frustration and boredom.

Moreover, Madigan (2010), argues that games facilitating immersion, either establish a vibrant mental model of the game environment, for example through multi-sensory information or a griping theme and narrative, or develop a consistency between the elements of the game by keeping the game environment coherent to the narrative and having the puzzles propel it. As such, many scholars using Escape Rooms for educational purposes, like Pinard (2018, p.1), Nicholson (2016, p. 12) and Clarke et al. (2017, p.80), support that puzzles have to make sense in terms of the theme, the narrative, the equipment and the learning objectives. Even though each puzzle can be subjected to its own internal logic, it can become integral with the rest of the game, only if its logic is well-balanced with that of the entire game environment.

One more characteristic of a puzzle is that it can be solved through the assistance of clues. As Clare states, “clues help players solve puzzles by providing them with a reference point which supports the logic of the puzzle and is based off of the theme.” (2015, p.624). Even though a clue could be any object in the room, from a coloured pencil to a random picture on the wall, it still needs to make sense in relevance to the challenge.

In addition to this, a puzzle can create an element of surprise to astonish or startle the students. For this to be successful, Nicholson (2016, p.11) advises the surprise to be something unexpected or even improbable, as well as something coherent with the theme, which will be comprehensible to the students later on.

Last but not least, a puzzle remains latent, until the point when the participants interact with it. Even though it is already setup in the room, a puzzle requires the players’ engagement to make it relevant (Clare, 2015, p.613).

Types of puzzles and materials

When designing an Escape Room, it is up to you, as an educator-designer, to determine what types of puzzles to include in the game, based on the educational objectives set at the beginning, the target group and the overarching theme and narrative. Equally important is to keep in mind the available resources you have, as well as the overall Escape Room time-limitation, in order not to go overboard and create non-feasible puzzles.

Typically, a well-structured game experience includes various forms of puzzles with the objective of engaging people with different skills and ways of thinking. For example, a series of puzzles could be composed by a mathematical puzzle, a puzzle based on a music sequence, some hidden items and a riddle, thus appealing to mathematical learners, musical ones, kinaesthetic ones and verbal ones. Drawing on Nicholson’s research, who surveyed 175 professional Escape Room facilities from around the globe, the professor has identified and listed 31 types of Escape Room puzzles (2015, pp.19-20). Below, you can find the most widespread ones:

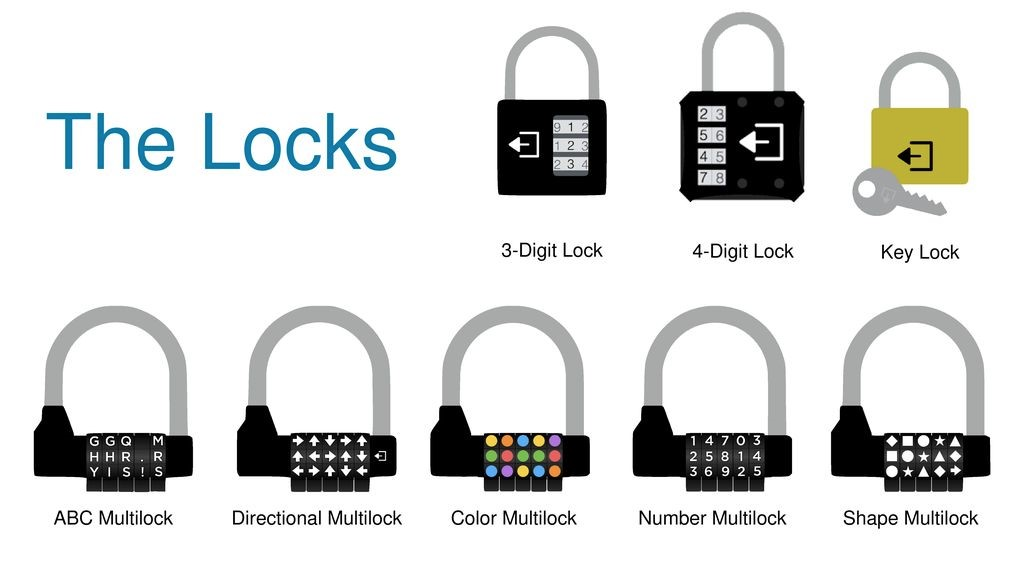

Lock type puzzles:

This is one of the most frequently encountered type of puzzles, where the reward is hidden away in an item, locked with some of the following examples of locks (image 1). The clues in the room help the players find the right key/code.

1

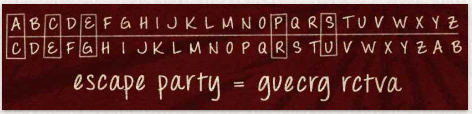

Code type puzzles:

Another type of common puzzles are custom codes and ciphers in the form of encrypted messages, such as Morse code, Braille, Pigpen cipher, or a Caesar cipher (where instead of beginning the alphabet with A, you start, for example with C, and shift the alphabet accordingly; see image 2). Below you can find a list of code examples (image 3):

2

3

Written puzzles:

A third form of puzzles are written texts, such as:

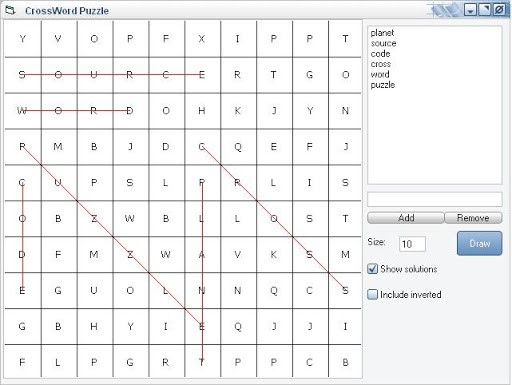

– Crossword puzzles (image 4);

4

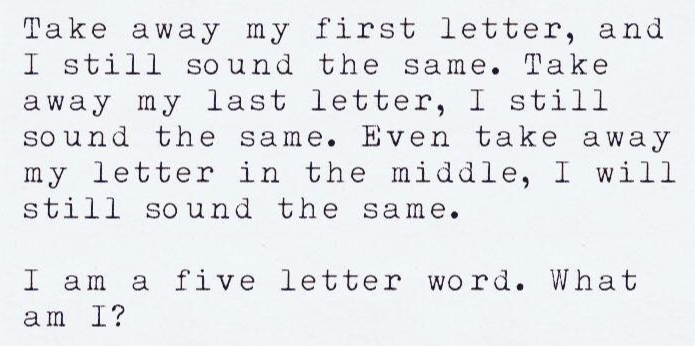

– Riddles (image 5);

5

Answer: Empty

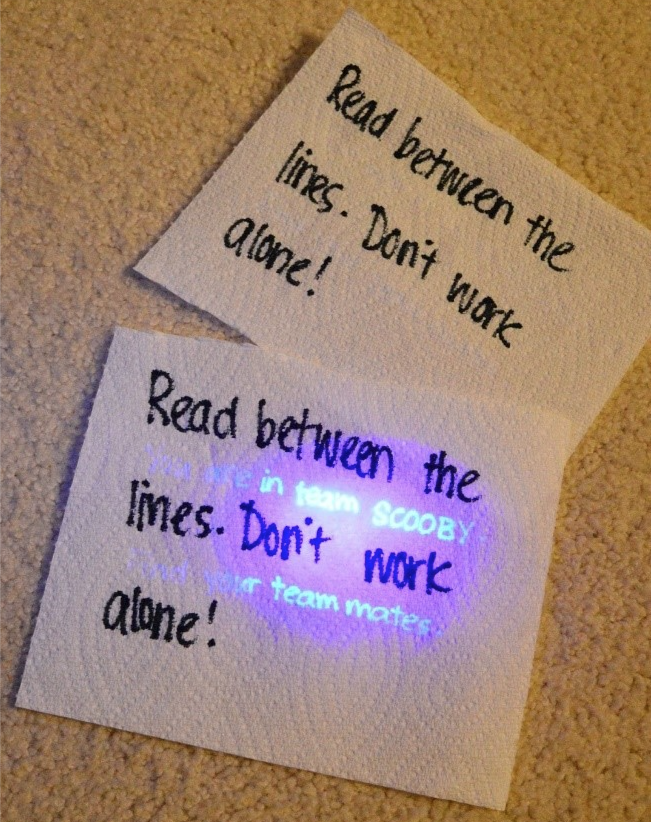

– Hidden text visible with an Ultraviolet blacklight (image 6);

6

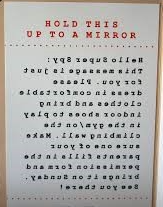

– Reversed text, discernible through a mirror (image 7).

7

Additionally, written texts can include hidden clues like:

– Certain words missing a letter, which can result to a password;

– Particular words or letter being capitalized;

– Specific words or letters marked in bold, color or highlighted.

Puzzles based on patterns:

A fourth type of puzzles are the ones based on detecting patterns in the room. These include, for instance:

– extracting numbers from images or counting the number of sides of geometrical shapes to retrieve a code (image 8);

8

“Gummy bear count: 6 red, 2 orange, 4 yellow, 5 green, and 4 white. Combine that with a hint elsewhere of “Red Orange Yellow Green” gummy bears leads to a code of 6245” (Escape Room Tips, 2020).

– paying attention to repeated themes, such as finding the same book in a Room library 4 times, while the rest of the books are unique;

– noticing the same mysterious symbol over 2 objects (ex. a key and a door), which insinuates that the two are linked in some way.

Mathematical puzzles:

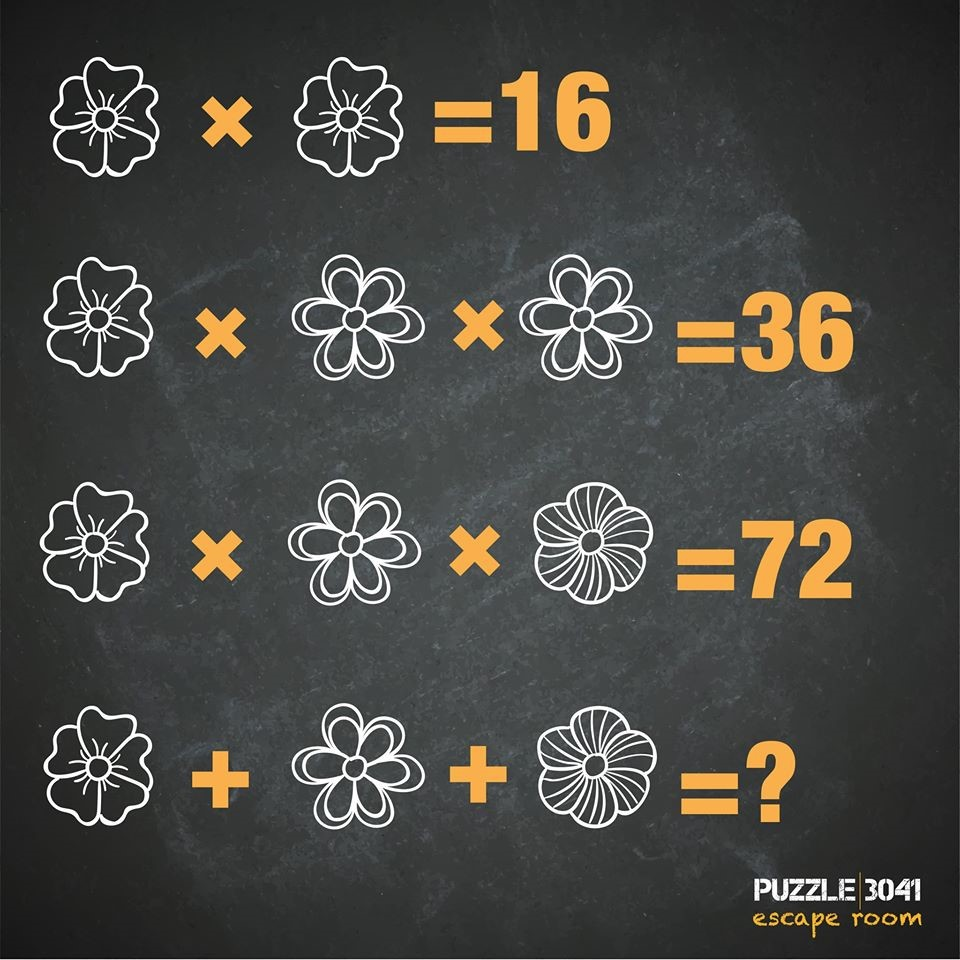

An additional type of puzzles is the one based on mathematics and related concepts, such as equations, algebra and abstract logic (ex. Sudoku). These puzzles don’t necessarily have to delve into complicated mathematical notions; they normally require the players to solve a straightforward equation (image 9) or perform some sort of manipulation.

9

Physical puzzles:

The final type of puzzles analysed in this lesson are physical puzzles, in the sense of activities that require players to search around the room or use their fine motor skills (such as hand-eye coordination). Some examples of these kinds of puzzles could be the following:

– looking for items in odd places or hidden within the room;

– retrieving items that are out of reach by climbing up a ladder;

– assembling a physical object (ex. a jigsaw puzzle);

– using fine motor skills (ex. undoing a knot, shooting a target).