Table of Contents

1. Educational objectives

Educational objectives of scenario A:

- Physics, Theme 4 – ‘Waves and signals – ‘Mechanical waves’. (Ministère de l’Éducation nationale, 2019b): Students will work on the different types of mechanical waves, the notions of frequency and wavelengths. Having a good comprehension of these notions constitutes the first educational objective of this scenario.

- Biology, Theme 1 – ‘The Earth, Life and organisation of living things’ – ‘Genetic information, its transmission, its expression, its variation’ (Ministère de l’Éducation nationale, 2019c): Students will work on DNA structure and sequences, which constitutes the second educational objective.

- Additionally, this scenario could include notions from music education, mathematics, technology

- Communication, active listening, digital skills

Educational objectives of scenario B:

This scenario has been created with the aspiration to empower girls to pursue a career in STEAM, by presenting them with roles models of famous women scientists.

- Mathematics, Theme 1 – Algebra and Theme 5 – Algorithmic and programming. (Ministère de l’Éducation nationale, 2019a): Students will work on sequences and series and cultivate their knowledge on programming.

- Additionally, this scenario could include notions from engineering, fine arts, history

- Collaboration, reasoning skills

2. Background topic

Topic of scenario A: Nowadays, in a conservatory. Students are working on their recitals, rehearsing their next performances or relaxing in the hall. Different kinds of music, coming from different instruments, are heard echoing in the building.

Topic of scenario B: Nowadays, in a science museum. The museum’s next exhibition – on women scientists – is almost ready to open. It displays many paintings, tools and devices which have belonged to the aforementioned scientists. (Fenaert, 2020)

3. Scenario

Scenario A: A valuable instrument has been stolen. Police officers – played by the students – enter the school. The culprit is still inside the building. The chief inspector decides to lock the building for an hour, with everybody inside, giving the officers time to identify the missing instrument and identify the thief. After tracing the instrument, the police officers will conduct a DNA analysis on clues found on it, so as to identify and arrest the culprit before s/he succeeds to escape

Scenario B: Two hours before the inauguration of a museum exhibition, the director realizes that one of the objects loaned by a private collector has not been showcased. There is no explanation about it, and nobody in the museum seems to know its utility. A group of friends, IT specialists and historians – the students –, who travelled to the museum especially for the opening of the exhibition, offer their help and knowledge to find the missing information regarding the artefact. They have an hour ahead of them before the crowd starts entering the museum. For the purpose of this scenario, the mysterious object will be Ada Lovelace’s ‘Diagram for the Computation by the Engine of the numbers of Bernouilli’, published in Sketch of The Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage by Luigi Menabrea (Ada Lovelace, 2020). This diagram is perceived to be the first computer program. (Gregersen, n.d.)

4. Puzzles

4.1. Puzzles’ features and components

According to Wiemker and al. (2015), Escape Rooms’ puzzles in their simplest form are made of three components: a challenge, a solution and a reward, giving either a clue which unlocks the next puzzle or the next puzzle itself.

- A puzzle must be static, up until the participants engage with it.

- It should create surprise, either by integrating an element unlikely to happen or unexpected. Alternatively, a surprise could be caused by an element that will make sense at a later stage.

- It should be logical and clear. Participants should be able to understand the output of the puzzle.

- It should be challenging, without being too complicated, so that participants can remain in Csikszentmihalyi’s (1996) state of “flow”. It is described as the ideal state of mind for players: a moment where the mind is set only on the goal and fully immersed in the story.

- To deal efficiently with difficulties that players could encounter, it is essential to set up clues, which constitute – again, according to Clare (2016) – the final component of a puzzle. Clues can take virtually any form: a drawing, a sound, a piece of furniture, etc.

4.2. Puzzles’ forms

4.3. Puzzles’ sequences

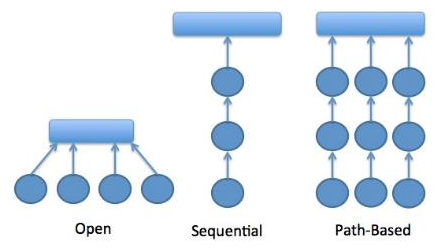

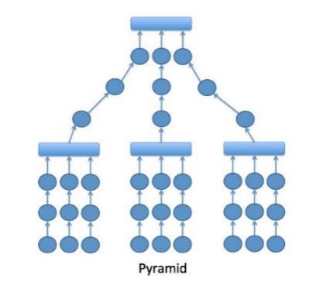

Once puzzles are created, the next important step is their sequencing. Each series should be carefully thought out and planned. Nicholson’s survey (2015) allowed him to isolate four general types of sequences, which he called: open path, sequential path, path-based and hybrid models (e.g. pyramid).

4.4. Tips for good puzzles

4.5. Adaptations for SLDs

- Use an adapted font (Arial, Century Gothic, OpenDys), in sizes 12 to 14, with a 1.5 line spacing.

- Reduce the number of tasks that require writing and diversify the types of puzzles.

- Give explicit guidelines and break instructions in several simple sentences.

- Avoid red-herrings and give clues one puzzle at a time. For example, avoid giving a clue for the last puzzle as a reward for the first one. If you wish to do so, creating a colour code to link puzzles with clues could be a solution.

- Focus on logic rather than memory

- Make great use of visual elements

- Choose puzzle types that foster collaboration in order to get players to help each other.

- Avoid difficult physical manipulations/use of fine motor skills

- Provide support when tasks require space management skills

4.6. Examples of puzzles for STEAM and role models for girls

Puzzle idea 1 for scenario A: The push of a button triggers a succession of notes. Successfully repeating the notes’ sequence on a keyboard (either a virtual or a real one), releases a key. (ex: given by the game master)

Remember to stop any other sound in the room while the sequence is playing to avoid distractions.

Puzzle idea 2 for Scenario A: Write down a DNA sequence. Leave some of the nucleotides blank. The nucleotides to be found will create a code.

Remember to write with big, clear letters. If you are printing it, use the fonts given above. You could also use Legos instead of paper. Associate one Lego colour to a nucleotide and build a sequence with it.

Puzzle idea for scenario B: Print pictures/paintings of several famous women scientists and inventors. Write a short description of their work aside. Stick everything on the wall to create an exhibition. Place a crossword in a safe, locked with an ABC multilock (for more information regarding the different types of locks, please refer to Grain 13, IO3). Link the riddles to the scientists’ descriptions. Colour several boxes on the crossword grid. Completing the crossword will reveal the code, indicated by the coloured squares. (Fenaert, 2020)

Make sure that descriptions are written in black, OpenDys or Arial, size 12, with a 1.5 spacing. Align left. Use white paper.

More examples of this can be found in Chapter 6, which considers ways of making STEAM escape rooms inclusive and educative regarding gender equality.