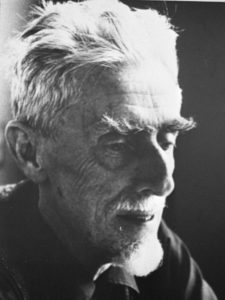

Maurits Cornelis Escher

He was a Dutch graphic designer, an artist, an engraver of extraordinary talent, but he did not study mathematics or geometry, nor did he have any particular scientific knowledge. On the contrary, his school career is decidedly lackluster. Yet, in 1961 the prestigious American magazine Scientific American, a point of reference in the academic world, published an article on Escher’s mathematical art, putting a work on the cover. How is it possible? His works, which seem to shape the harmonies of nature, have attracted the attention of many mathematicians from all over the world. When he arrives in Italy he is fascinated by the beauty and variety of the landscape. His first visual illusions that deceive perception, the transformations of geometric shapes that become fish, birds or other strange animals, arise precisely from the desire to represent in visible form the complexity and regularity of the world around us. Then, in 1936, during his second trip to Spain to the Alhambra, he discovers the ability of the Arabs to decorate surfaces with geometric shapes that can be replicated indefinitely, and it is a real illumination.

The link between Escher and science is therefore indissoluble; the artist, through the language of art, captures the rational soul of the universe and represents it. Scholars, for their part, fascinated by being able to “see” the laws of mathematics and geometry, are struck by his work. And art and science, for once, come to speak the same language.